Let me start with an extremely pedantic point:

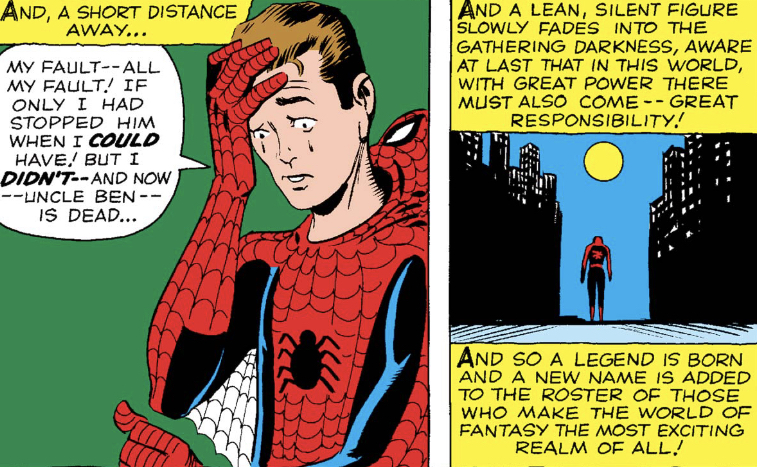

It wasn’t “with great power comes great responsibility,” it was “with great power there must also come great responsibility.”

This is mostly just nerdy trivia, but Spider-Man: No Way Home got it right and in the process pointed out something really interesting about the difference and what it says about holding those in power accountable.

From here on the spoilers are going to get plenty deep for Spider-Man: No Way Home. Stop now if that’s not your thing.

In No Way Home as May dies she tells Peter the original wording: “with great power there must also come great responsibility.” There’s a couple of interesting aspects to this:

1: How Did Peter Become Spider-Man?

There’s no indication Peter’s ever heard that phrase before. Most retellings put those words in Ben’s mouth, which raises some questions about MCU Peter Parker. Did he have an Uncle Ben? Did Ben die? Was that death related to Peter’s (miss-)use of his powers?

The typical story is something like “Peter gets bitten by a weird spider, gets powers, uses those powers for personal gain as a wrestler or something, passes up an opportunity to stop a thief who end up shooting Uncle Ben.”

We (thankfully) never got an on-screen origin story for MCU Spider-Man, so if he never had an Uncle Ben was he just a hero because it was the right thing to do? Was there no tragedy in his closet?

It’s actually kind of refreshing to have a hero not become a hero because they were taught a lesson by their tragedy but instead just do what good they can. Which leads to our second point:

2: Does Spider-Man know what the other MCU heroes do in their other movies?

May’s delivery of the less-famous original line defines the overall theme and driving action of the movie.

Peter chooses to not send a bunch of people who are causing him (and others) harm back to their lives because they would all die there. Which raises the question: does Peter know what happens to all the other villains in Marvel movies?

Malekith? Dead. Thanos? Dead. Helmut Zemo? Dead. Ultron? Dead. Claw? Dead. Red Skull? Dead. Killmonger1? Dead.

I could go on. And sure, a lot of these are “comics-dead” not “dead-dead,” but a lot of them are also directly killed or allowed to die by the heroes.

There are a few exceptions. The Vulture (from the first MCU Spider-Man movie) lives. Loki did/does2 too. But for the most part MCU villains are one-movie deals and the cleanest way to write them out is to give them a (as the scripts tend to suggest) deserved death.

This probably makes sense for movies. If you need to draw audiences in for two hours a few times a year you need something fresh to throw at them (unless they really clamored for more—looking at you Tom Hiddelston).

But it ends up not feeling very much like the comics. Someone like Malekith goes from being someone with a long complicated history with Thor to that one weird elf that showed up that one time. (I mean, Malekith in the MCU is the worst anyway, but the same goes for Thanos at a slightly larger scale.)

No Way Home is implicitly a refutation of the earlier Spider-Man movies. It literally spends most of its run time trying to change the outcomes of those films, to have a hero who is not about punishing deeds but instead about helping people. And it ends up saying something about the rest of the MCU too.

Faster, Stronger, Better Ideas

While I can’t think of a notable time Grant Morrison has written Spider-Man No Way Home is a very Morrison movie. As he wrote in Supergods:

Before it was a Bomb, the Bomb was an Idea. Superman, however, was a Faster, Stronger, Better Idea.

No Way Home is about a better idea of (MCU) superheroes. It frames that as an indirect critique of earlier Spider-Man movies, but those arguments go just as well against basically everyone else in the MCU.

And that resonates with the original wording of “with great power…” to such a degree that it might have been an intentional choice to use that wording.

“With great power comes great responsibility” is a statement of fact. Those that have great power get responsibility (somehow?) automatically. It suggests an accountability somewhere beyond this world.

“With great power there must also come great responsibility” is an imperative. It says that when someone gets great power they need to be held responsible for it. It still doesn’t say who should do that, but I’d say that means it falls to the reader.

I have no idea if Lee or Ditko were making a choice with that wording or if this is just my reading of it, but to me the differences between those framings also describe a gap in a lot of modern life.

If great responsibility follows from great power as a matter of fact then when someone accumulates great power we say they are responsible for some things and move along. Later, sure, we may need to hold them accountable for the responsibility they now have, but we don’t need to change anything when they get that power.

If great responsibility must come with great power then when someone accumulates great power we need to take action to hold them responsible, from the start. The imperative is to outline their responsibility then and there (and hopefully in a way that doesn’t involve lessons by way of dead relatives.)

The common wording has passive responsibility. The original wording has active responsibility.

We tend to treat our governments, corporations, and billionaires as if, by fact of their power, they have responsibility. But they, all too often, do not act as if they have that responsibility. And since that responsibility is kind of a passive thing that came with their power it’s too easy for them to avoid.

We need to be the must that attaches the active responsibility to the power around us.